Git tutorial (2023 FE edition)

This tutorial is created specifically for faculty enrichment purpose, please adjust accordingly if you’re not using it in this context.

Git is a popular version control software to manage codes, especially in a collaborative environment.

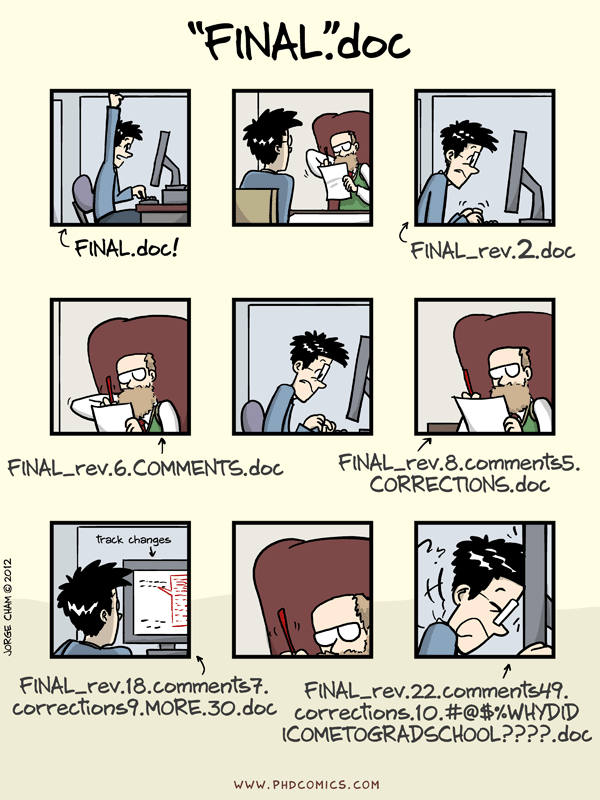

Here is a comic from “Piled Higher and Deeper” by Jorge Cham regarding version control:

Git allows us to make changes to our code, and say if we didn’t like the changes, we can always go back to the older versions of the code. In a collaborative environment, our colleagues can make changes to our codes, and we can track who’s made what changes to the code, and undo it if necessary. If all of these sounds familiar, yes it does feel like we that track changes function in say Microsoft Word, or the version control function available in Dropbox. The difference is that you can designate a folder as your “Git repository”, and you decide which file inside this folder get version controlled.

Git allows us to make changes to our code, and say if we didn’t like the changes, we can always go back to the older versions of the code. In a collaborative environment, our colleagues can make changes to our codes, and we can track who’s made what changes to the code, and undo it if necessary. If all of these sounds familiar, yes it does feel like we that track changes function in say Microsoft Word, or the version control function available in Dropbox. The difference is that you can designate a folder as your “Git repository”, and you decide which file inside this folder get version controlled.

While Git is a software that lives inside your computer, GitHub is an internet hosting provider that can host your Git repository. For example, many Python packages such as pandas is hosted on GitHub. Our FE examples and website are also hosted in GitHub, here and here.

In this tutorial, we will:

- Fork the FE example repository to our personal account.

- Setup our Quest environment to communicate with GitHub.

- Clone the forked repository to Quest.

- Commit some of our changes, and push to GitHub.

Forking

We start with going to the GitHub repository of our FE-2023-examples repository. Make sure that you are signed into your own GitHub account at this point. Look for the buttons near the top right section of the page: Watch, Fork and Star. Clicking on the Fork button will lead you to a page about “Create a new fork”. By clicking on the Create fork button, you would have created a fork of the FE-2023-examples to your own account.

What does this forking mean? Essentially you copy and paste the existing repository to your account. This allows you to make changes on the repository, without affecting the main repository. Often, we don’t necessarily have editing access to a repository, or we simply don’t want to accidentally make any changes to the “main” one. Forking allows us to make modification to the codes without that fear! Furthermore, we can, e.g., make meaningful changes to the repository, and then ask the original repository’s owner to review and adapt our changes to their repository through a pull request. If the original repository made some updates, we can also synchronize our forked repository with its upstream.

Setting up Quest environment for GitHub

Now that we have a forked repository, we want to bring the repository to our work machine, known as “clone”. Since this involves getting our work machine to talk to GitHub, we need to make sure this process is secured. Typically, we would enter our username and password when prompted, however, this process becomes cumbersome as GitHub added additional security measure. As a result, we find it easiest to add SSH keys of our Quest environment to GitHub.

You can find instruction to do them in details:

Here’s a condensed version of it…

- Login to your Quest via SSH

- Paste the following text

ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C "your_email@example.com"to your terminal, substitute the email address to the one you use for your GitHub.

- Press Enter when prompted (you unlikely need to change the file for the key).

- Choose a passphrase or leave it empty when prompted.

- Done with Part 1, now paste this

pbcopy < ~/.ssh/id_ed25519.pubto your terminal. This basically copy the content of the newly generated key to your clipboard. - In GitHub (go to

github.comin case youre lost), click on the top right corner which should display your profile photo. - ‘Settings’ -> ‘SSH and GPG keys’ -> ‘New SSH key’

- Paste into the

Keysection. Give your key a name in theTitle, sayQuest. - Click

Add SSH keyand… you should be done with this!

Clone repository

Let’s navigate back to the forked repository page in GitHub. You should see a green button that says “Code”. When you click on it, you can see 3 tabs: “Local”, “SSH” and “GitHub CLI”. Click on the “SSH” tab, and copy the URL that’s right below it.

Now go back to your terminal that’s SSH into Quest. Navigate to the desired directory that will receive the repository. The following command will clone your forked repository hosted in GitHub into Quest:

git clone <paste_your_url_here>If nothing goes wrong, you can check the content of your directory (e.g., by typing ls), and you should now see a new folder with the name of your repository (most likely FE-2023-examples). You have now cloned it to Quest!

Making changes and git commit

We make changes or add more files to our repository locally all the time. Git would take note of all these changes, but until we “commit” these changes, they would only remain a local change that can be discarded.

Let’s navigate to the repository itself, and type git status, which tells you the general status of your repository. For now, you’ll most likely see:

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

nothing to commit, working directory cleanIn this case, it is saying that your repository is synchronized with the one in GitHub, and that you’ve made no changes to the local repository yet.

Let’s start out by changing something and see what git does. Say, we can modify the README.md, adding a sentence after the first sentence of the README file, say “This is git status again. Now you’ll see this instead:

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: README.mdGit has been tracking the file README.md and it has detected changes in that file. While this is quite obvious to us what has changed, it is not always so when you working with lots of code. It is helpful to use following command to see what has changed in the file: git diff.

Next, to “commit” to the changes you made to README.md, we use git add to “stage” the file for changes. We don’t immediately commit changes in git, instead we put those changes in a “staging ground” first. Imagine you are sending documents to some government agencies for some application, you don’t immediately send one document (say in total you have four documents to send) out right? You might instead put the document in an envelope, and wait until you have all four documents inside the envelope before you seal it and send them off. Similar concept here where we “stage” the file(s) first before committing.

Once we stage the README.md, check git status again. Now you can see README.md turns green colour, and you see Changes to be committed now. We can commit the changes now, but we can also wait for more changes.

In this case, let’s create a new file, say a hello_world.py, with a line that prints out “Hello World!”. Now check git status again, and you can see that the new file appears in another section called Untracked files:. This file is new to git, and git is not currently tracking the changes to the file. It only starts tracking after you add and commit the file to your repository.

We can now also git add the hello world file. Check git status.

OK let’s say we are now satisfied with the changes we made so far. We are now ready to commit the staged file to our repository. To do so:

git commit -m "<your commit message here>"Typically we want to have a commit message that is short, and yet informative about your changes. Some softwares would even ask you to put a message with less than 50 characters. In this case, we can say Add my name to README and add hello world.

Now we committed our changes. To be sure, we can check git log. This log shows us all the commits that were done and by whom they were done, from the newest to the oldest. You should see your commit at the top of the log.

Now this commit is done locally, meaning that if you go to GitHub, you would not see any of your commit yet! You can also see that something like Your branch is ahead of 'origin/main' by 1 commit. in git status. This means that there’s 1 commit in your local git that is not captured by your remote git, i.e., GitHub. In order to synchronize, we can use git push. This basically “push” the commit to the remote repository in GitHub.

Now if you look over to your GitHub repository, you should see the commit there now with the corresponding changes!

These are some of the basics of git, let’s practice creating two more commits, 1 with changes to your hello world script, and 1 deleting your hello world script.

More Git?

There are more to git than all these, hopefully we get to learn more as we start using git more and more.

The software carpentry has a good tutorial for you to learn more about git.